Homo Sapiens Librorum

Were you born in the 20th century like me? This is a post about AI that mainly doesn't talk about AI at all. It's about you and I...

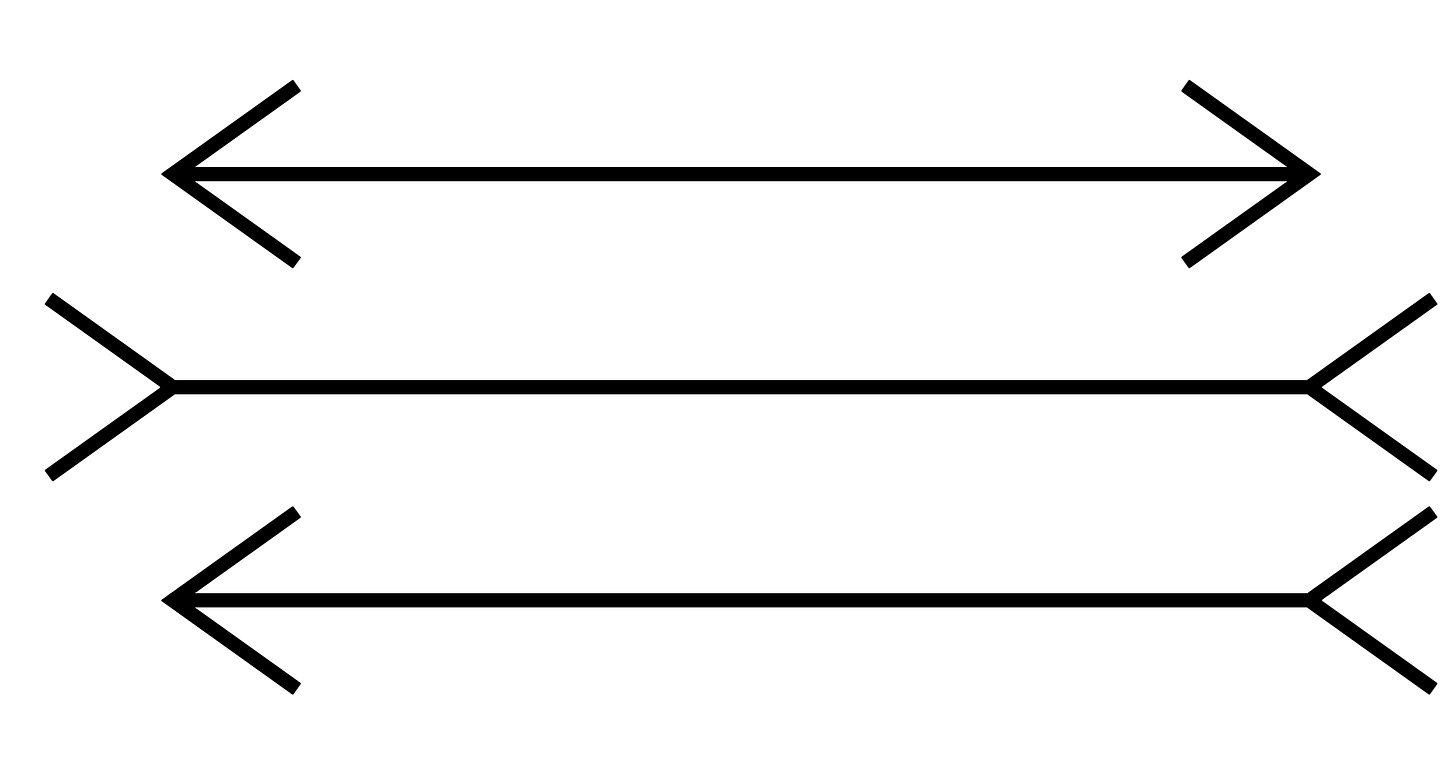

Hi there! it’s been a while… Which horizontal line is the longest?

If you’re cabled like most people, the middle one definitely looks longer than the other two. It’s call the Müller-Lyer illusion, coming to you live from 1889.

All three horizontal lines are of equal length of course, but that’s what’s really fascinating about human cognition: even after measuring these three lines and confirming they're identical in length, your brain refuses to accept it. Try again! That's not just stubbornness - it's a perfect demonstration of how deeply embedded our cognitive biases are. Even when we're aware of them, they don't simply disappear.

This is one of the most obvious ways I can think of that our brains trick us without our knowledge. While reading "Thinking, Fast and Slow" by Daniel Kahneman (an absolute must-read if you're curious about how your mind actually works), I stumbled upon the WEIRD people study. Its authors revealed something both obvious AND surprising, and also profound: most of what we think we know about human psychology and cognition comes from studying perhaps the least representative humans possible: the minutest fraction of the Homo genus you could think of - Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic college students. Imagine building your understanding of the entire human species by studying only the patrons of a single Starbucks on a university campus. I highly recommend the paper, if only for its introduction, by far the sauciest scientific literature I’ve come across!

Blast off!

I need to bring in Carl Sagan now, so I can lay out the stage of this article. The above photograph is called the "Pale Blue Dot", a humbling image of Earth taken by Voyager 1 from 3.7 billion miles away. Sagan wrote that "There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world." Today, I want to take you on a similar perspective-shifting journey, not through space but through time, to examine how we think about human cognition and education. Let’s start with a thought experiment…

Let's go about 3 or 4000 years in the past, maybe somewhere around the fertile crescent. Imagine a group of educators from this pre-literate oral society, you are one of them, and imagine that you're having a meeting… a faculty conclave I think it was called back then.

It so happens that writing was just invented, someone is explaining how it works and you’re trying to wrap your head around the concept. You’re not the only one confused, the most astute thinkers among the educators are silently contemplating the implications of such an unprecedented development. For the first time, human ideas can be laid down on a material object and travel through time and space. Little by little, there are a wide range of clamor and objections…

These weird little marks on this clay tablet are actually saying stuff? And most of the kids know how to use them already??

But, how can we know for sure they know the answer to a question, and that they haven’t just read it?

Won’t they use it to cheat?

Should we ban it?

In fact, we don’t really need to go through this thought experiment to get a window into some of our ancestors’ thinking. Plato conveniently tweeted about just that.

Plato’s Tweet

In Phaedrus, Plato records Socrates’ lament to the god who brought writing to mankind. Writing, Socrates argues, will create forgetfulness in the learner’s soul because people will no longer rely on memory. They’ll “trust external written characters” instead of truly internalizing knowledge, gaining the semblance of wisdom rather than its reality.

Fortunately for us, Plato did not heed his master’s advice. Instead, we can discuss Socrates’ opinions some 2,400 years later and on a continent he never knew existed. Socrates wasn’t alone in fearing that writing would dilute a core aspect of humanity—our ability to propagate knowledge through oral tradition. He was, of course, correct. Writing did fundamentally change the way humans think, communicate, and pass down wisdom. But the doors it opened—ideas traveling across centuries and continents—were so mind-boggling that opposing it was, in hindsight, utterly futile.

Do you think these imagined educators could have foreseen that they were living at the tail end of what we now commonly refer to as prehistory? They’re literally not part of history!

Cognitive Revolutions I & II: Literacy and the Printing Press

Fast-forward a few millennia, and scholars have examined the transformative effects of communication technologies on human cognition. Walter J. Ong, in Orality and Literacy (1982), explored the seismic shift from oral to literate societies. Oral cultures rely on memory and communal storytelling, creating dynamic, context-dependent understanding. Writing introduced abstraction, allowing ideas to be preserved, examined critically, and accumulated over time. This fostered individual, analytical thought and redefined social organization.

Derrick de Kerckhove and Charles J. Lumsden took this further in The Alphabet and the Brain (1987), suggesting that alphabetic writing promotes left-hemisphere brain dominance. Its sequential structure aligns with and reinforces analytical and logical thinking, contributing to the scientific and philosophical achievements of Western civilization. Then came the printing press. Marshall McLuhan’s The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962) showed how print amplified these changes, standardizing texts and encouraging individualism, rationalism, and linear thought. Print culture laid the foundation for modern science and the fragmentation of knowledge.

Each of these technologies transformed not only communication but also the very ways humans think and perceive reality. They brought structure to knowledge but also homogenized thought, limiting the diversity of cognition found in pre-literate societies. Yet, who would wish to go back?

The Digital Revolution

Now, compare my experience growing up in 1980s France with that of today’s American K-12 students. My world was defined by books, libraries, and scarcity of information. Students today inhabit a world of hyperlinks, videos, and instant access to a cosmic trove of knowledge. How has this shift shaped their cognition? Their very concept of information must be radically alien to mine.

Marc Prensky (2001) described today’s students as “digital natives,” contrasting them with their “digital immigrant” teachers—85% of whom formed their cognitive frameworks before broadband internet. Digital natives process information rapidly, multitask naturally, and favor interactivity, while traditional educational models remain linear and text-heavy. This mismatch may explain why students often disengage.

Neuroplasticity explains this divide. The brain’s ability to adapt to new environments peaks in youth and declines with age. Millennials like me bridged the pre- and post-internet worlds, adapting organically to each technological leap. Today’s children, born into the digital era - younger than YouTube - are cognitively distinct from their teachers. Here’s a graph to illustrate this.

Homo Sapiens Librorum

When I look at the graph above, I notice that my home got broadband internet right before the hump (1999), and that I bought my first laptop somewhat close to the top, albeit right after (2003). After that, and according to these researchers, my technology rich environment and education allowed me to seamlessly adopt each new technology while retaining the sense of what the world was like when I was growing up. It's hard to decide where the change happened, but it seems clear to me that humans younger than me who cannot fathom the pre-internet world, are of a slightly different subspecies than me and the overwhelming majority of my readers (at the time of writing, who knows!). I dubbed us Homo Sapiens Librorum, or "human of the books".

When I was growing up (and this will be true for anyone my age or older), information was scarce and organized overwhelmingly in books. The major world religions that shaped history, all systems of philosophy and law and science - everything was based on written documents. Back in the middle ages, books were rare luxury items accessible to just a few people. So when did my species arise? Was it the printing press, or rather the industrial revolution and mass alphabetization that produced humans such as me? We can split hairs all day long here, but I think we can agree that our particular kind of human did not exist 500 years ago. At this scale, I don't need to be any more precise, since Sapiens apparently developed the ability for language around 50,000 years ago, depending on estimates. This suggests that my kind of human represents less than 1% of human history and ended with me. Every part of my identity and my culture is owed to books. However, with the 21st century, information changed drastically in the way it is organized, and the internet is clearly defining this era as sure as the book did the one before.

So here's the real question: how qualified are we, the book people, to dictate what's crucial for children who will live in a world we can barely imagine? In the same vein as those early educators from our thought experiment, maybe we should think twice about deciding what is or isn't acceptable in today's children's education.

Plato vs Diogenes

I invoked Plato earlier in this text and I'd like to bring him back around to let you in on an ancient intellectual joust I learned about in one of Idriss Aberkane’s latest conferences. Apparently, Plato defined human beings as "featherless bipeds." When he heard this, Diogenes brought a plucked chicken to Plato's school and exclaimed "here's Plato's human!"

Throughout human history, each major shift in communication technology has built on and accelerated the previous ones. Literacy needed oral language. Printing needed literacy. Computers and the internet needed the scientific revolution that books made possible. And now, AI and Large Language Models wouldn't exist without the vast amount of data that emerged from Web 2.0 and humanity's collective contributions to the internet.

So while it is tempting for us - Homo Sapiens Librorum, to pontificate about the importance of reading, writing, and books, we're essentially doing what Plato did - defining humans by what we are, not what we could become. We're telling our students they're featherless bipeds when they might be growing wings.

Every technological leap has faced valid criticism about what might be lost: memory in oral societies, depth of thought with writing, attention span with digital media. Yet each transformation has expanded human potential far beyond these fears. As Eric Hoffer presciently noted:

"In times of change learners inherit the earth; while the learned find themselves beautifully equipped to deal with a world that no longer exists."

The chicken Diogenes brought wasn't just a clever prop - it was a declaration about the danger of limiting definitions. Today's AI is our contemporary philosophical chicken, challenging us to see beyond our current limitations. And just like Plato's definition revealed more about him than about human nature, our anxiety about AI might say more about us than about the future we're trying to understand.

Bravo! Well said. I love this perspective and I agree. Also being a millennial, I often feel foreign to the internet native generation (that I teach). I do believe that we as teachers (and parents) should adapt to our students in every way, the other way around would result in lack of growth. It will be interesting to see how this major shift in access to knowledge will shape the world, and how generations to come process knowledge.